ABAP Exception Pitfalls

Like many programming languages, ABAP supports exceptions. However, using class-based exceptions in ABAP has various pitfalls which should be avoided.

Defining Exceptions

When defining a class-based exceptions in ABAP, you have to pick a root exception class from which to inherit. ABAP has three different root exception classes: CX_STATIC_CHECK, CX_DYNAMIC_CHECK and CX_NO_CHECK. Choosing the right base class is of utmost importance.

CX_STATIC_CHECK is a checked exception which means that the compiler checks whether the exception was handled correctly. Whenever a checked exception could occur, it either needs to be passed to the caller of the method by placing it in the method’s signature or it needs to be caught in a catch block. If it is neither caught nor declared in the signature, the ABAP compiler will raise a warning. If you ignore this warning and the exception is thrown at runtime, your program will crash and you’ll receive a ST22 short dump.

Like CX_STATIC_CHECK, CX_DYNAMIC_CHECK can be placed in a method signature. However, you will not receive a warning when you neither catch nor pass on an exception inheriting from CX_DYNAMIC_CHECK. This sounds like a regular unchecked exception in other programming languages, but it is not the same. CX_DYNAMIC_CHECK has a special quirk: It gets transformed into an exception of type CX_NO_HANDLER if it is not included in every method signature along the call hierarchy. This can lead to a rather peculiar behavior. For example: Let’s assume that method A calls method B which in turn calls method C. C has included a dynamic exception (i.e., an exception inheriting from CX_DYNAMIC_CHECK) in its signature, but B has not and also does not contain a catch block. However, A has a catch block matching the dynamic exception thrown in C. Unfortunately, this catch block will not work: As B does not include the exception in its signature, the originally raised exception gets transformed into a CX_NO_HANDLER exception and therefore doesn’t match the catch block included in method A. To catch the exception, B either has to include it in its signature or A has to start catching CX_NO_HANDLER instead. This behavior makes dynamic exceptions difficult to use. We have to pay close attention to the method signatures as forgetting to include the dynamic exception at any point can break existing exception handling. As there are no warnings for unhandled dynamic exceptions, it is rather easy to forget to include them especially when refactoring. Interestingly, most of ABAP’s system exceptions are dynamic exceptions for reasons probably only known to the ABAP language group.

The last exception root class is CX_NO_CHECK. It is a straight forward unchecked exception implementation. Exception handling of unchecked exceptions is not enforced and they will not get converted to CX_NO_HANDLER. However, in any ABAP release before 7.55, it is impossible to add an unchecked exception to a method signature. So, when using an older release, any caller of a method has to either check the ABAP Doc or the source code to find out what unchecked exceptions are thrown by that method. So which exception root class should you use? I strongly recommend against using CX_DYNAMIC_CHECK. The transformation to CX_NO_HANDLER turns this exception into a strange hybrid between unchecked and checked exceptions which makes exception handling more difficult while providing no benefits. That leaves us with either CX_STATIC_CHECK or CX_NO_CHECK.

CX_STATIC_CHECK should only be used if both of these conditions are true:

- Every caller of the method absolutely has to handle or pass on the exception

- Every caller of the method is most likely able to handle the exception in a meaningful way.

If any of the conditions above is false, you should use CX_NO_CHECK as base class. Note that using an unchecked exception does not imply that nobody should catch it. It merely implies that any caller has the option of catching it. Good examples for unchecked exceptions are illegal-input-exceptions or data-not-found-exceptions. The latter should not be checked exceptions as this would force callers who absolutely know that the data they are looking for will be found (for example, because they inserted it a few lines before) to write a catch block for an exception which will never occur. From my experience, most properly designed exceptions will be unchecked exceptions as the criteria for good checked exceptions are rarely fulfilled.

When defining your exceptions, it is often a good idea to use fine-grained exceptions. That means that you should be able to tell the root cause from the name of the exception. An exception called CX_MY_API_ILLEGAL_GUID is much more expressive than an exception called CX_MY_API_ERROR. Using a generic exception for multiple different error cases is not a good idea. While it reduces the number of exceptions you have to define, it makes it rather difficult for a caller to react to different errors in different ways. To tell each error apart, you would have to introduce some kind of internal codes which get carried by the exception. While this is doable, it is harder to handle in the code. Also, it is very difficult to define meaningful error texts for a generic exception. Generic phrases like “an error has occurred” are not very helpful. The flipside of using many fine-grained exceptions is that a caller might have to catch multiple exceptions. As you are able to catch more than one exception in a catch block in ABAP this may be a tad inconvenient but usually is not too much of a hassle. If you want your callers to be able to handle all your exceptions in a generic way, consider creating a generic exception superclass from which all your exceptions are inheriting. That way you get the best of both worlds.

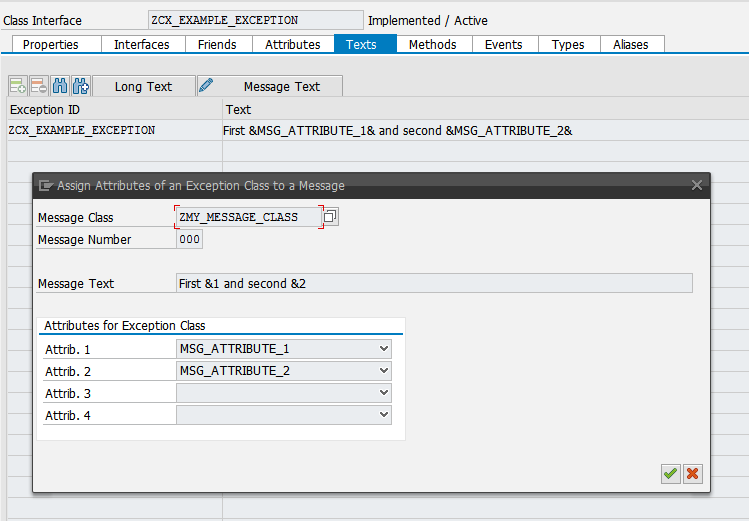

Whenever you create an exception in ABAP, you should make sure that it carries a meaningful and translatable text. After all, each caller should get their exceptions in their preferred language, otherwise they might not be able to tell what is going on. By default, the texts you attach to an exception are not translatable. To rectify this, your exception has to implement the IF_T100_MESSAGE interface. This interface enables you to attach a message defined in a message class as the exception text. You can also define some attributes which can be used in the message. While it is possible to define more than one such text on an exception, it is usually not necessary if you opted to use fine-grained exceptions. The process of making exceptions translatable is rather buggy in the old-school SE80 transaction. From my experience, you are better off defining the exception in the ABAP development tools (also called ABAP in Eclipse). There, you can define an exception in a fully text-based way, with less “magic” involved. The following code snippet shows how to define such an exception in the ABAP development tools:

CLASS zcx_example_exception DEFINITION

PUBLIC

INHERITING FROM cx_no_check

FINAL

CREATE PUBLIC .

PUBLIC SECTION.

INTERFACES if_t100_message .

CONSTANTS:

BEGIN OF zcx_example_exception,

msgid TYPE symsgid VALUE 'ZMY_MESSAGE_CLASS',

msgno TYPE symsgno VALUE '000',

attr1 TYPE scx_attrname VALUE 'MSG_ATTRIBUTE_1',

attr2 TYPE scx_attrname VALUE 'MSG_ATTRIBUTE_2',

attr3 TYPE scx_attrname VALUE '',

attr4 TYPE scx_attrname VALUE '',

END OF zcx_example_exception .

DATA msg_attribute_1 TYPE string .

DATA msg_attribute_2 TYPE string .

METHODS constructor

IMPORTING

!textid LIKE if_t100_message=>t100key OPTIONAL

!previous LIKE previous OPTIONAL

!attribute1 TYPE string OPTIONAL

!attribute2 TYPE string OPTIONAL

!attribute3 TYPE string OPTIONAL

!attribute4 TYPE string OPTIONAL .

PROTECTED SECTION.

PRIVATE SECTION.

ENDCLASS.

CLASS zcx_example_exception IMPLEMENTATION.

METHOD constructor.

CALL METHOD super->constructor

EXPORTING

previous = previous.

me->msg_attribute_1 = attribute1 .

me->msg_attribute_2 = attribute2 .

CLEAR me->textid.

IF textid IS INITIAL.

if_t100_message~t100key = zcx_example_exception.

ELSE.

if_t100_message~t100key = textid.

ENDIF.

ENDMETHOD.

ENDCLASS.In SE80, it will look like this:

Note that the attributes have to be public for this to work. Now, all you have to do is pass the attributes when raising the exception like this:

RAISE EXCEPTION TYPE zcx_example_exception

EXPORTING

attribute1 = 'first'

attribute2 = 'second'.Handling Exceptions

I have a seen a lot of improper exception handling during my time as an ABAP developer. The most notorious one is the empty catch block. This means that whenever an exception occurs, the code just continues running. While this can be fine if the try block only contains a single method call which is expected to fail in certain situations, it also can be very dangerous if it occurs in a big try block as the application then enters an undefined state. An exception implies that only parts of the code were executed successfully. When the application is forced to keep running afterwards, its behavior might be off. Maybe it’s going to crash later, due to a CX_SY_REF_IS_INITIAL exception, maybe it completes successfully, but wrote incomplete or corrupted data in the process. Ignoring an exception like that can be very dangerous and should be avoided. Often, empty catch blocks are provoked by an improper exception definition. Using a checked exception, when an unchecked would be correct, forces the caller to handle the exception in some way which increases the temptation of just adding an empty catch block. Also, if the exception doesn’t communicate what exactly went wrong or when it will occur, the caller will be hard-pressed to handle it in a meaningful way and may just default to an empty catch block again.

A variant of the empty catch block is the insufficient catch block. In it some kind of message is raised which documents the error, but the application continues to run. In addition to potentially putting the system into an undefined state, this pattern also makes it very easy to hide the root cause of an error. If we want the program to continue to run and not lose critical information, we need to preserve as much information from the raised exception as possible. That means that our message should at least contain the text of the raised exception as well as any available information on previously raised exceptions. This information is available via various properties and methods on the exception object. Sadly, I’m not aware of any convenient way of converting a caught exception into a message which is as expressive as a short dump. That means we will have to manually parse the exception properties to build a good error message.

Due to the problems outlined in the last two paragraphs, it is often a good idea to just let the program crash. ABAP short dumps are a great help for diagnosing problems and a crashed program at least doesn’t corrupt any database data. If you’re unsure how to handle an exception, my recommendation is to not handle it at all.

Conclusion

As we’ve seen, there a quite a few pitfalls when defining exceptions in ABAP. To sum up, you should:

- Inherit from either CX_STATIC_CHECK or from CX_NO_CHECK.

- Attach a translatable and expressive text to each exception.

- Only catch an exception if you can handle it in a meaningful way.

- Make sure that you don’t mask any errors when catching an exception.

If you liked this blog post, please share it with someone. You can also follow me on Twitter/X.